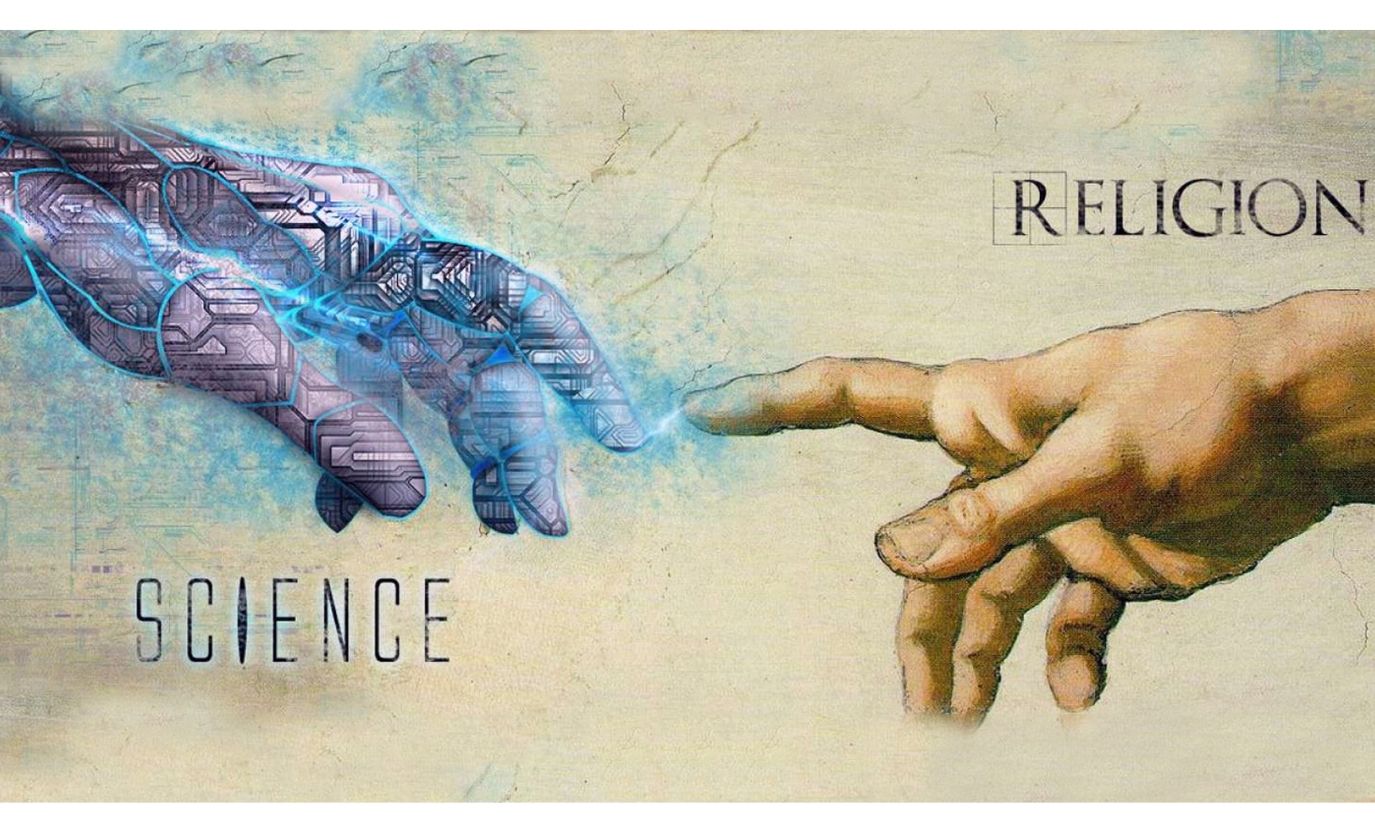

The need to explore the relationship between Marxism and religion stems from a situation marked by communal polarization and the threats posed to the secular state. In this context, it is crucial to examine how ordinary peasants and workers engage with the state's approach to culture and religion. The central question is whether people can successfully define and live according to their own culture, religion, and secular beliefs, and how this ties into the larger goal of overthrowing both capitalism and communalism.

It is important to examine life and Marx's writings from a fresh perspective. Marx was born into a Jewish family in Trier, located in southern Germany, and his father was a rabbi. Later in life, when he had children, his family converted to Protestantism to escape anti-Semitism. Additionally, it is noteworthy that Friedrich Engels wrote a comprehensive booklet titled Revolutionary Christianity, which discusses the Book of Revelation, the oldest text in the New Testament (republished by Critical Quest, New Delhi, in 2017).

Marx’s own writings on religion primarily include the "Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right" and an article titled "On the Jewish Question." He was aligned with the Young Hegelians, a group of followers of the philosopher Friedrich Wilhelm Hegel, who critiqued the concept of the "World Spirit," which they regarded as the source of dialectical thinking. They sought a strictly secular approach to dialectics, rejecting Hegel’s notion of the "Weltgeist" (World Spirit).

In the chapter on the Jewish Question, Marx critiqued religion as the "opiate of the people," suggesting that the proletariat must move beyond it because it clouds their perceptions and becomes "the flower of the chain." The real challenge lies in breaking these chains and freeing themselves.

During the 1950s, the revolution in Cuba marked a new direction for Latin America. Marxists had to reconcile their beliefs with Roman Catholicism. The 1960s brought a revolutionary atmosphere among students and workers in both Europe and Latin America, which had a global impact on Marxism. In India, Marxist state governments were established in Kerala and West Bengal, and the Vietnam War served as a significant inspiration, showcasing how Vietnamese workers and peasants successfully resisted the powerful American forces in the mid-1970s.

This period also saw an initiative to "learn from the Third World," which highlighted the experiences of small peasants, unorganized sector workers, women peasants, and worker alliances. In the 1990s, the Ambedkar Centenary and the publication of his works provided a remarkable impetus for Dalits, women, and Backward Classes (BCs). My discussions with Dileep Kamat in the mid-1970s focused on the revolutionary potential of popular culture.

The interest in popular culture has provided a deeper understanding of the challenges faced by Dalits, highlighting the need to address issues surrounding religious conversion. For instance, why did Dr. Ambedkar choose to convert to Buddhism? Similarly, the conversion of Pandita Ramabai raises significant questions about the role of women in various religions, which ties into broader issues of reservation policies, violence, and political participation. For more insights, refer to Uma Chakravarty's book Rewriting History: A Life and Times of Pandita Ramabai (New Delhi: Zubaan, 1995), as well as my article titled "Religion, Resistance and Liberation" in the compilation Marxist Feminist Theories and Struggles Today: Essential Writings on Intersectionality, Postcolonialism, and Ecofeminism, edited by Kayat Fakir, Diana Mulinari, and Nora Raetzel (London: Zed Press, 2020).

Furthermore, anti-conversion laws have led to new forms of violence in various states, particularly in Odisha and Chhattisgarh.

This raises important questions about secularism. I am uncertain whether 'Hindustan' can be redefined merely as a geographical term associated with a major river, especially while communal leaders are attempting to establish "Hinduism" as the state religion. The struggle for secularism is a shared responsibility of all religious and irreligious communities in our country. It necessitates a rediscovery of humanitarian, nature-friendly, and liberating values in religions and popular cultures, allowing us to celebrate our commonalities while appreciating our differences. Tamil Nadu has a strong history in this regard that spans over a hundred years, but even that legacy is now under threat.

The question of how fascism can come to power through democratic means yet prove so difficult to dismantle is a significant concern for me. I was born at the end of World War II, and my generation has not received clear answers regarding the systematic extermination of six million Jews, as well as gypsies, resistance fighters, communists, and transgender individuals, who were murdered in gas chambers. Our parents’ generation has insisted that they "did not know" what was happening.

How did the nation that spearheaded Gandhi's nonviolent freedom struggle come to possess nuclear weapons, cleverly codenaming the test detonation in Rajasthan "the Buddha is Smiling"? How can we eliminate this threat? Marx did not foresee the world wars, the emergence of state capitalism in post-revolutionary countries, or the environmental destruction caused by relentless industrial "development." We must depend on the struggles of peasants, workers in the unorganized sector, Dalits, Backward Classes (BCs), and women, utilizing all their cultural resources to advance the struggle.

Antonio Gramsci, in his Prison Notebooks, emphasized the importance of a Cultural Revolution. He believed that not only workers, but civil society as a whole, could contribute to cultural transformation. This is a goal worth pursuing. We need cultural studies at all levels. In 959, the people’s publishing house published a book titled Lokayata, which rediscovered the connections between Sankhya philosophy and Buddhism, reflecting a process also found in the Bhagavad Gita.

Currently, in Madurai, we are nearing the end of the Chitra Festival, which is celebrated by thousands of people along the riverbed of the Vaigai River and in countless temples. Lord Kallazhagar even visits a mosque during this time. As long as the people's culture stands against communalism, there is hope for the future.

Gabriele Dietrich

Madurai

Become a member

Get the latest news right in your inbox. We never spam!

Comments

No Comments