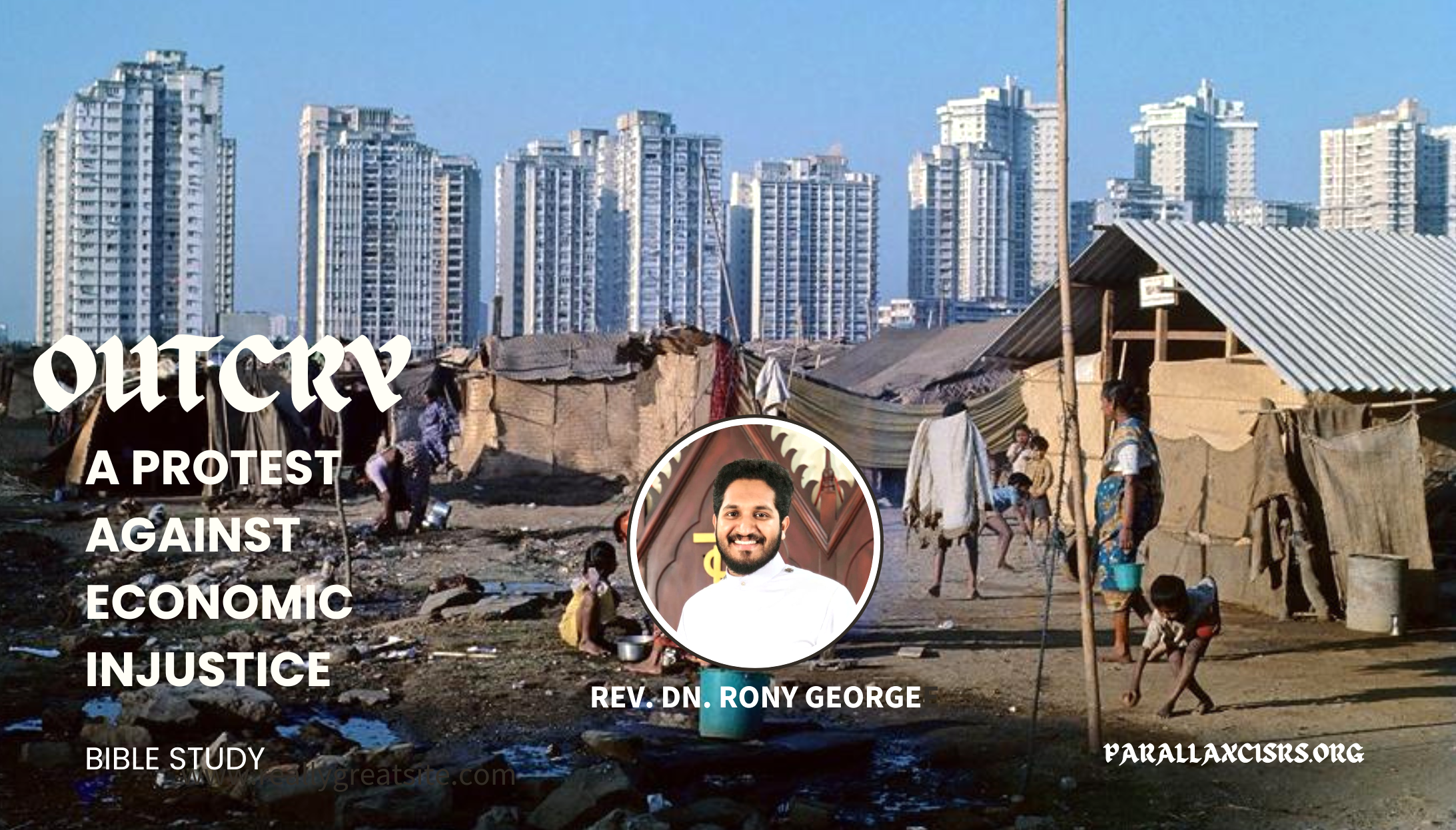

What will help the world of finance/economy to transform? While I do not have an answer on that, I want to share why the economy/finance needs a serious and radical transformation. Or an understanding of where we stand today is fundamental to thinking about what needs to be changed.

It’s an understatement to say that our economy is in shambles now. The credit goes back to the plans and programs we followed based on the neoliberal economic policies, but then taken to an all-time low by this government, where cronyism, corruption, fraud and vulgar accumulation of wealth are legally sanctioned, valorized and made it into a virtue in itself.

Where has that led us to? Look at the economic indicators today. The unemployment rate is the highest in 45 years. GDP growth had been on a downward slide before 2019. With COVID-19, and with the nationwide lockdown, that slide turned into a fall, sending India to negative growth for the first time in 40 years. Retail inflation rates are still high, impacting the food and essential goods of common people. We can look at rising household debt, wealth inequality, rampant accumulation of wealth and power, jobless growth, and the crisis of livelihoods, and all these will tell us the economic state in which we are.

Demonetisation and the goods and services tax regime have broken the backbone of the informal sector, which employs nearly 90% of the workforce, and small traders, something which they never recovered from. The GST regime has also crippled the state governments in terms of their agility to find resources of their own to meet their needs, posing a serious threat to fiscal federalism.

What does wealth inequality tell us? There has been an obscene concentration of wealth in the country over the past few decades. The gap has widened with what looks like a K-shaped recovery post-Covid resulting in extreme inequality. The top 1% in India has almost 60% of private individual wealth. According to the latest Oxfam report, the wealth of billionaires increased from Rs 23 trillion to Rs 53 trillion during the pandemic. The number of Indian billionaires grew from 102 to 142, while 84 per cent of households in the country suffered a decline in their income. In the Global Hunger Index, the country slipped down to 107 out of 121 countries.

This is in addition to the government's crackdown on civil society, which criminalizes dissent and deliberately stirs up communal polarization on a large scale. Furthermore, it compromises all key institutions in the country that have historically played a role in speaking truth to power and holding authorities accountable. All of these are essential to this regime to promote and sustain the dream of ‘Amrit Kaal.’

While a Bofors rocked government decades back, a Rafale jet deal, or Electoral Bonds or PM Cares or even a Hindenburg report is not even looked at with the seriousness it deserves and pursued to their logical end by the media or judiciary and the voices of the opposition parties are either expunged or they are disqualified. The secrecy which is made to accept and silence bought over these matters with the ED and IT raids has further exacerbated the gap of accountability.

Look at our banks and other financial institutions. Saddled by huge NPAs, the government had to resort to two things to make things look better. Massive write-offs of bad loans, amounting to over Rs. 11 trillion in the past 6 years were one of them. The majority of these bad loans belonged to big corporations and not students, farmers or small traders, all of whom are harassed by recovery agents and many driven to take their lives. The other thing the government did to ensure that the banks maintain the required capital was to recapitalize the banks. Govt recapitalized the banks with over Rs. 3 trillion of taxpayers’ money in the past five fiscals. Not only that banks lost common people’s money in the bad loans, the government used taxpayers’ money to recapitalize the banks, making it a double whammy for the common people.

While political interference and cronyism are key reasons for these massive bad loans, one of the other reasons is the lack of a due diligence process independently by the banks, including looking at social and environmental risks, but currently, they rely only on the environment clearance or forest clearance of the government.

Apart from the traditional investors, the new breed of investors is the sovereign wealth funds, private equity and venture capital funds. A study done last year by our team reveals that just the Sovereign Wealth Funds, Real Estate Investment Trusts and Private Equity Funds alone invested $146 bn between 2016 and 2020 in sectors like Oil & Gas, RE projects, real estate and large infrastructure projects. All of which are outside the purview of any regulatory mechanism to bring in some accountability in them. There are Indian PE and VC investors, though in comparison to their foreign counterparts, they are small.

A question which is asked at us often is why private investments should come under public scrutiny. We believe that without three key components, private entities can never make massive profits – tax subsidies, tax holidays and tax wavers – all of which could have been used for the welfare of the citizens. Two, land and other resources at a very low price, if not for free and finally, public financial institutions largely bear the costs and take risks for their businesses.

While there is some focus on Indian commercial banks, however inadequate it is, what is done by Indian Exim Bank, using taxpayers’ money in other countries, is seldom reported or discussed. Until 2019, it invested over $24 billion in Asia and Africa, fuelling land grabbing, massively promoting agro-business, in energy projects and other large infrastructure projects. The impacts of these investments on people, climate, forests or waterbodies are rarely reported or discussed in India.

Privatisation of public services and institutions is at an all-time high. Institutions built decades back using public money were allowed to die slowly by the policymakers. Take the example of state-owned BSNL. They were never allowed to bid for 4G when it was introduced, saying that the private parties will not have a level playing ground. The situation remains the same even now with 5G. And we all crib about the poor services of BSNL and switch to private players. Or look at public sector banks. In the State Bank of India, while the VRS was encouraged, no recruitments are done in the past few years that the per employee customers in SBI is 1900 while in HDFC Bank, it is only 501, ICICI is 353 and Axis Bank 325. How can we expect a better service from SBI in comparison with its private counterparts? And poor service is often cited as a reason why SBI should be privatized.

While we are looking at these issues, one cannot forget where it all stems from – institutions like the World Bank and IMF, platforms like G20 and its Financial Stability Board, all of which design and prescribe policies to emerging economies like India, which are taken as God’s word by successive governments. That they are undemocratic institutions and platforms, are made for pushing the interests of the rich countries and their private corporate interests, and history telling us that countries which followed their prescription had fallen into debt traps and it took decades for them to recover, even if in a limited way, are not taken into consideration by our policymakers. India, being the Presidency of G20 this year, is not leaving any stones unturned, no walls unpainted and no hoardings left without the photos of Viswaguru, to make it a grand political spectacle using taxpayers’ money, is unashamedly evicting slums, removing thousands of street vendors and waste-pickers from the cities wherever G20 events are happening for security and beautification purposes.

What’s the way out? As I said in the beginning I do not have easy answers. The economy is too dear to common people, affecting all walks of life that they cannot afford to leave it to the policymakers and experts alone to take decisions for them. It always puzzled us that India where we have a long history of many organisations working on labour issues, human rights, minority, gender and children’s rights for the past many decades does not have such longstanding work on finance and economy. It is time that we do it.

As Jayati Ghosh says in a slightly different context, but it can be adapted in our situation as well, “All this cries out for a 21st century version of a New Deal and a Marshall plan, ideally as part of a co-ordinated Global Green New Deal. The US New Deal, as well as the Marshall Plan, had three crucial aspects: recovery, redistribution and regulation. The plan for recovery relied on massive fiscal stimulus, and was characterised by speed, scale and generosity. Redistribution was achieved through fiscal policies, through employment generation and through regulation of capital, labour and land markets. All of these were crucial in reviving global demand in mid-20th century – but all of these are currently missing from the policy agenda today."

While it looks daunting, the collective efforts of people have resulted in some changes. 30 years back when principles of accountability were at an early stage, the struggle in the Narmada Valley forced the World Bank out of Sardar Sarovar Project and the accountability mechanism Inspection Panel was instituted. Many in the audience have been a part of that struggle for decades. A people’s campaign in 2018 forced the government to withdraw the Financial Resolution and Depositors Insurance (FRDI) Bill – one of the three Bills this government was forced to withdraw. The Bill would have made depositors money to bail a bank out in case of its collapse. A bunch of fisher people from Kutch, Gujarat successfully challenged World Bank’s immunity in US Supreme Court, allowing communities around the world to legally challenge the World Bank Group in any court.

Any engagement with the government to transform the economy or financial institutions requires a democratic space. At a time when that is missing, fighting for economic transformation requires fighting for a democratic space.

This is an edited version of a talk at the Conversations on Exploring New Imaginaries of Environmental Justice, held during the 25-year celebrations of the Environment Support Group in Bengaluru. Joe Athialy is the director of the Centre for Financial Accountability, a Delhi-based research and campaign organization.

Become a member

Get the latest news right in your inbox. We never spam!

Comments

No Comments