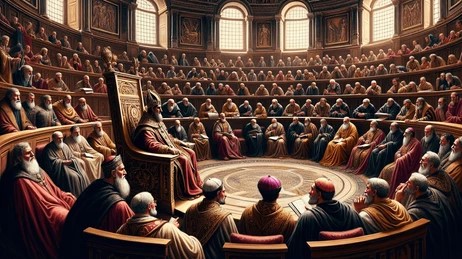

This year 2025 we join the global ecumenical movement in celebrating the 1700th anniversary of the world’s first ecumenical council, the Council of Nicaea of 325, a key historic moment in the history of Christian faith and for the ongoing ecumenical pilgrimage today. It was at this council that the historic Nicene Creed took its shape and was later reaffirmed with some more additions in 381 at Constantinople. The significance of the creed at Nicaea is that it had affirmed the ‘coequality’ of God and Jesus in terms of divinity, the first and second persons of Trinity. This notion of ‘coequality’ which is homoousia in Greek has several colonial overtones with the empire theology of its time and context.

When I start reading the Nicene Creed from my Dalit decolonial theological perspectives, it calls me to be critical of the powers and coloniality attached to it. Affirming of Christ as begotten from God and ascending into heaven did not disturb the empire’s power and domination. He was made man- except that Jesus has become a man; there is a conscious omission of Jesus’ prophetic mission in the Nicene Creed. There is no mention of Jesus’ alternative kingship riding a donkey to Jerusalem, no mention of his healings and transformation of people, no mention of Jesus’ cleansing of the temple and critiquing the powers, neither there is any mention of the kingdom of God that Jesus preached and practiced in the creedal affirmations. Jesus’ creative liberative mission against unjust structures of the empire and injustices of his times was not formulated in the creed. What we see here is more of a high-Christology that legitimizes power centers.

The coloniality of the Nicene Creed is further noticed in making the understanding of salvation about heaven with no relevance to the life on the earth. Clatworthy was succinct when he questions the concept of salvation in the Nicene Creed, particularly the words ‘for us and for our salvation.’ He says, “in the Hebrew scriptures the two great moments of salvation were escape from Egypt and return from exile. In the New Testament the Greek word for salvation is also the word for healing, welfare and prosperity. The fourth century changes made salvation all about heaven, and getting to it when you die by escaping from the devil’s clutches.” The empire theology’s emphasis on ‘Christ the Pantocrator’—the ruler of all, in contrast to Jesus the alternative king as mentioned in the gospels, whose rule was about defiance to the empire, was the theology that drove the context of Nicene creed. Clatworthy is right when he says, “what Christian emperors needed was a theology that approved of their rule, their warmongering, their economic exploitation and their suppression of dissent” (Imperial Theology and the Nicene Creed, 2021).

However, in the context of caste discriminations in India, affirming Nicene creed offers to Dalit Christians a liberative strength to experience the love of the Trinitarian God—a communitarian God, who offers grace, solidarity and liberation through God’s own act for us in the universe, and not through the merit or karma of human beings. Decolonial reading of Nicene Creed from Dalit theology’s perspective, therefore is an expression of such a celebration of context, celebration of theology, and a celebration of liberation, where mediations of grace happen abundantly among and between them, inviting us to give up our parochialism and seeking mutual accountability for the cause of justice and liberation of all. So, what does this translation of homoousia mean to our Dalit Christian communities? Well, to our Dalit Christian communities, we believe in the unity of God the Father and God the Son, and we believe it is the Dalit Jesus who is in unity with Dalit Father. It is the broken/crucified/risen Dalit Jesus who is in unity with Dalit Father/creator/maker. The human Jesus who has pitched God’s tent among us in our Dalit peta (colonies) is in unity with God the Father, is how we Dalit Christians understand it.

When Dalits have already been projected as who are ‘not born from the body of God,’ this “denied transcendence” further pushes the Dalits to marginalization and exclusion. Thus, the theology of homoousia in a way affirms Dalit theological understanding of God and Jesus and thereby rejects the casteist notion of untouchability and unholiness. This then leads us to argue for a decolonized understanding of God where homoousia provides the idea of an open unity of transcendence and immanence of God –-a relational God. Such a shift towards relationality in theology would help to decolonize God, who is not at all “a beyond-God” but rapture from within. It provides impetus for their day-today liberative actions challenging domination and hegemony in the society. As Arvind P. Nirmal expounds, God of Dalits is a servant God who suffers the victimization and cries out form the cross, but offers a revolutionary dream of the coming resurrection which embodied and enmattered. This view provides impetus for formulating new theologies, liturgies and scriptural hermeneutics of liberation as the marginalized people are concerned. .

One of the difficul.es of colonial episteme of Nicene Creed for Dalit Christians is that the separation of the divine substance to the rest of the creation, where the lives and struggles of Dalits does not matter in the understanding of the divine. On the contrary, Dalit decolonial piquancy will revise the Nicene Creeed with a vision of a relational God and relational world. If Nicene Creed has left an open-ended ambiguity to further engage with the meanings of faith, God, divinity, humanity etc. new creeds will keep arising as the time, context and situation demands. The project of Nicene Creed on its 1700th anniversary has not finished and has not closed, rather has opened up in a new way inviting more creative creeds to be put forth so that our Christian faith stays relevant, applicable and meaningful. The work of Nicene Creed is an unfinished job, and more creative engagements with it are invited.

Rev. Dr. Raj Bharat Patta is an ordained minister of the Andhra Evangelical Lutheran Church in India and currently serves as a recognized and regarded minister of the Methodist Church in the UK working in the United Stockport Circute.

Become a member

Get the latest news right in your inbox. We never spam!

Comments

No Comments